by TRA

Why is the

Pentacon Six called an “SLR”?

Q: “Why is the

Pentacon Six called an “SLR” (a “Single Lens

Reflex”) when it takes so many different lenses?”

A:

The name “Single Lens Reflex” is used to

differentiate between this camera type and the type

known as a “Twin Lens Reflex” (“TLR”). I

hope that the following diagram and photographs will

make this clear.

| The Twin Lens

Reflex |

||||||||

|

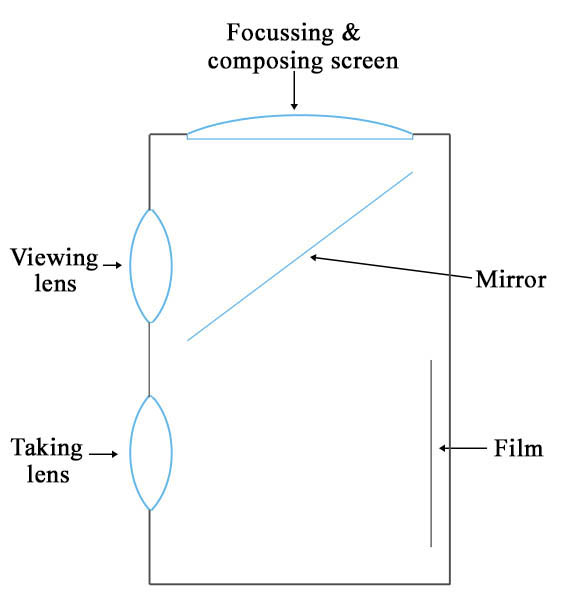

Firstly, the basic principle

of all “Reflex” cameras is that they have a

mirror that reflects the image from a lens onto

a glass screen that is used for focussing and

composing.

The outline sketch to the

right illustrates the principle of the Twin Lens

Reflex camera.

Here, we are looking side-on at a box. We can see that a mirror in the top half of the box reflects the image from a lens that we will call the “viewing lens” up onto a ground-glass screen at the top of the box, used for focussing and composing the image. The photographer holds the camera at chest height, or higher, leans forward and looks down onto the focussing screen. In a real camera, there would be flaps standing up round the focussing screen, to shield it from light coming from around it. The taking lens is in the bottom half of the box, and directs the image straight onto the film, which is held in place near the back of the box. Both lenses are mounted onto the same front component of the box, and this can be moved backwards and forwards within the box, to achieve focus. Distances are so precisely calculated that when the image on the focussing screen is sharp, the image on the film will be, too. Compared with the Single Lens Reflex camera, the Twin Lens Reflex camera has some advantages and some disadvantages:

|

|

[tlr_dia.jpg] |

||||||

| No

doubt there are other advantages and disadvantages

of Twin Lens Reflex cameras. However, most

of these cameras are fine, even superb, and they

are often very satisfying instruments to work

with. |

||||||||

| The Single Lens Reflex |

||

|

To illustrate the Single

Lens Reflex principle, I am using photographs

that I have taken of an immediate predecessor of

the Pentacon Six, a Praktisix, cut in

half. Such cameras were occasionally

supplied for use in camera shop showcases and

windows, to explain the SLR principle while at

the same time promoting the camera.

We can see that

this particular camera has the 80mm Biometar

lens and a non-metering pentaprism on the top

of the camera. The five elements of the

lens are clearly visible. Underneath the pentaprism is a large rectangular lens that is within the prism housing. This gathers the light rays from the focussing screen, which is immediately below it and is part of the camera. Below the focussing screen, we can see the mirror, which is at approximately 45°, just as in the TLR diagram above. Behind the mirror, just in from

the camera back, we can see the pressure plate

that holds the film flat. As it has been

cut in half, we can see its bright, metal

surface as a narrow, vertical line. We

cannot see the shutter, which consists of two

flat cloth curtains that would normally be

just in front of the film, to prevent light

from reaching it. Unlike the Twin Lens

Reflex, the Single Lens Reflex has a

single lens which must fulfill two functions:

|

|

[halfp6.jpg] |

| The laser pen was

taped to a mini tripod, but tended to sag, so it

was “steadied” by my free hand. With my

right hand firing the shutter on the camera that

took the picture, my left hand was not that

steady. Because of the low ambient light

level required to show up the laser, the exposure

was 30 seconds. In consequence of these two

factors, the resulting laser line was somewhat

diffuse. |

||

| In the first picture, we can see

the laser light as a bright red point going

through the five elements of the lens, slightly

above the centre point. It then strikes the

mirror and is deflected up through 90° to the

focussing screen. It traverses the focussing

screen and goes through the condenser lens at the

base of the prism, then straight up to the top of

the prism. From there, it is reflected

forward and down to the lower front face of the

prism. This part of its trajectory has not

come out clearly in this image. However, we

can see how the laser light is reflected from that

lower front face of the prism straight back to the

rear surface of the prism, as a horizontal line in

this image. From the rear surface of the

prism, it strikes the eyepiece lens on the back of

the prism, through which the image is viewed by

the photographer. (But if you try to

replicate this experiment, do not let the

laser light shine into your eye, or anyone

else’s! It may cause permanent damage to

your sight or to theirs!) |

|

When we fire the shutter on an

SLR, the mirror has to flip up to a fully

horizontal position at the top of the chamber, so

that the image being projected by the lens can

strike the film (the focal plane shutter having

opened). In this sectional model of the

Praktisix, the mirror mechanism unsurprisingly no

longer works. I could have “swung” the

picture of the mirror up in imaging

software. It would then have been

immediately below the focussing screen, preventing

any light from entering the camera from

above. However, I have not done that, but by

moving the laser pointer slightly towards the

right-hand side of the camera (viewed from the

front of the camera), I have managed to get the

laser beam to brush past the edge of the half of

the mirror (which should at this point not be

there!) and onto the pressure plate, thus

approximately simulating what happens when the

film is exposed. Note that while the image

is being projected onto the film, it is no longer

being reflected up to the focussing screen, which

is why no image is seen in the viewfinder during

the exposure. |

[laserhalf_01.jpg] |

[laserhalf_04.jpg] |

|

The principal advantages of the SLR (and the newer digital SLRs, or “DSLRs”) are:

- As regards composition, what you see is what you get. No more tops of heads cut off in photos.

- For close-up work, especially, the advantage is enormous, since macro and micro photography are essentially impossible with a TLR.

- The immense majority of SLRs (but, surprisingly, not all of them) have interchangeable lenses, resulting in the one camera becoming suitable for virtually all types of photography (e.g., wide-angle panoramic shots, portraits taken with slightly longer lenses, wildlife and sports photography with extreme telephoto lenses, etc.).

- Each time you change a lens, you only

change one lens, not two.

(And each time you buy a lens, you only have to buy

one, not a pair.)

Since the late 1960s, SLRs have been the most

popular cameras with most professional photographers

(especially in photojournalism, sports and wildlife

photography) and with most enthusiastic amateurs.

Most film-based SLRs were for 35mm film, but SLRs in

larger formats (like the Pentacon Six!) are capable of

producing images that are visibly superior to many

equivalent images taken with 35mm SLRS. The

preference for SLRs (and digital SLRs) continues with

many professionals towards the end of the second decade

of the 21st century.

© TRA First published: January 2018